Man Missing 90% of His Brain Lives a Normal Life

In 2007, The Lancet journal presented a remarkable case of a 44-year-old French man who was missing 90% of his brain. What made this discovery truly extraordinary was that, despite his condition, the man had been living a relatively normal life. Although his IQ was slightly below average at 75, he was socially competent, married, raising two children, and working as a civil servant.

So, what exactly was happening inside this man’s brain? Let’s dive in.

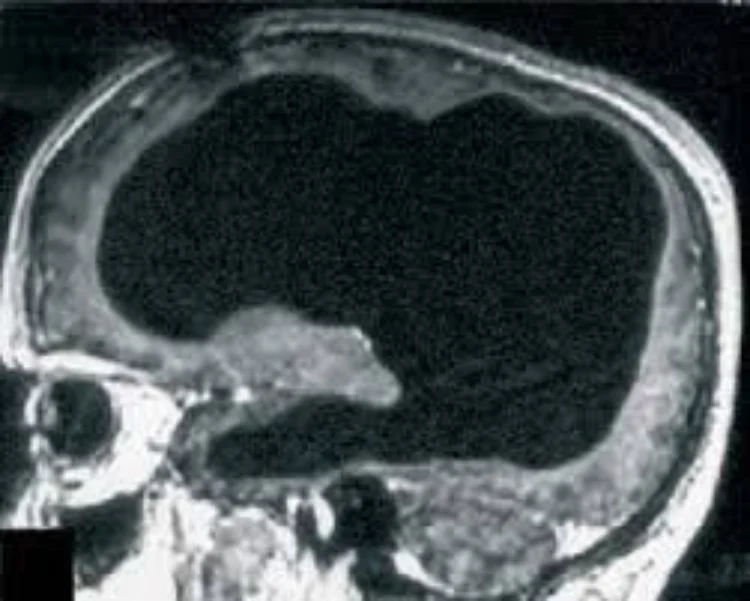

The French man had a condition called “hydrocephalus,” where about 90% of his brain tissue was lost due to an accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid in his skull.

The man’s medical history revealed that he was diagnosed with hydrocephalus at just six months old.

Normally, the brain and spinal cord are surrounded by a clear liquid called cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This fluid acts like a cushion, protecting the brain and the spinal cord. In hydrocephalus, something goes wrong with the way this fluid circulates or is absorbed, leading to a build-up.

He had surgery to insert a ventriculoatrial shunt, a tube that drains the excess cerebrospinal fluid from the brain into the heart.

At 14, he suffered ataxia, a condition where poor muscle control results in problems with coordination and balance. Also, he felt weak in his left leg. The doctors decided that the implanted shunts needed revision (either repair or replacement), and after the procedure, all the symptoms went away.

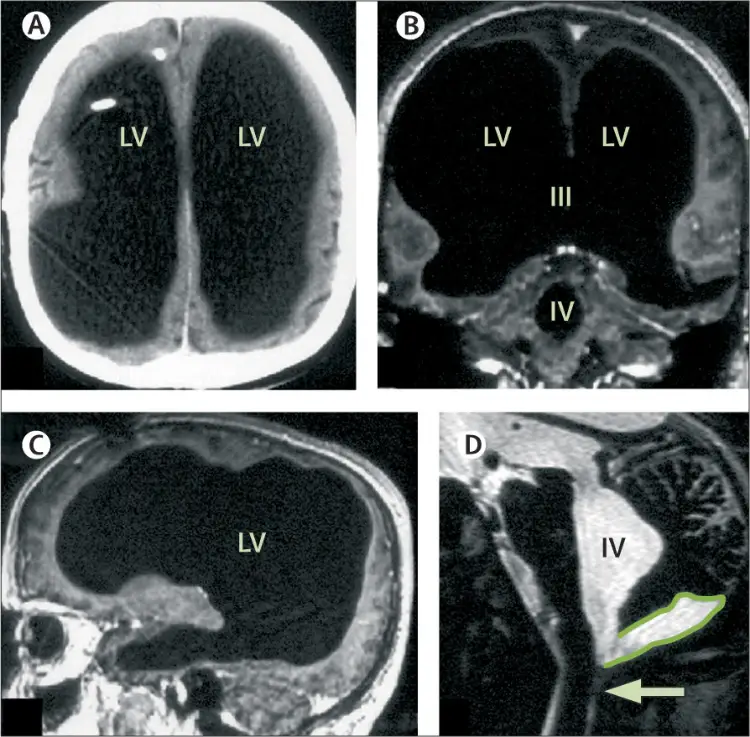

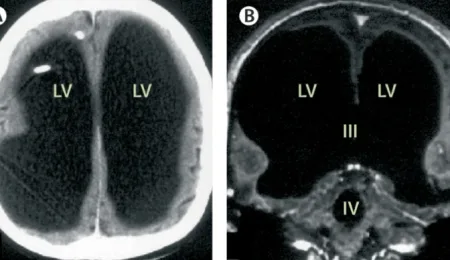

However, when the man turned 44, the weakness in his left leg returned, prompting doctors to conduct a CT scan and MRI. These revealed that his skull was missing about 75% to 90% of its brain tissue. It was replaced by massively enlarged lateral ventricles, which are typically small chambers holding the cerebrospinal fluid.

Doctors diagnosed him with non-communicating hydrocephalus. This means that the fluid in the brain wasn’t able to flow properly, likely because of a blockage.

The man’s brain coped with the loss of brain tissues by adapting and building new neural connections.

The man’s brain was reduced to a thin layer of tissue, affecting the frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes of both sides of his brain. Normally, damage to these regions would result in significant impairments.

However, the gaping discovery was made more astonishing by the man’s ability to function as a normal human being.

As he exhibited no unusual symptoms, the case highlights the power of neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to adapt and reorganize itself throughout life, especially in response to trauma or injury. When part of the brain is compromised, other regions can form new neural connections to take over the lost functions.

In this man’s case, his brain gradually compensated for the missing tissue, allowing him to lead a normal, functional life despite the astonishing extent of his brain damage.