MIT’s Latest Swarm of Robotic Bees Can Artificially Pollinate Flowers

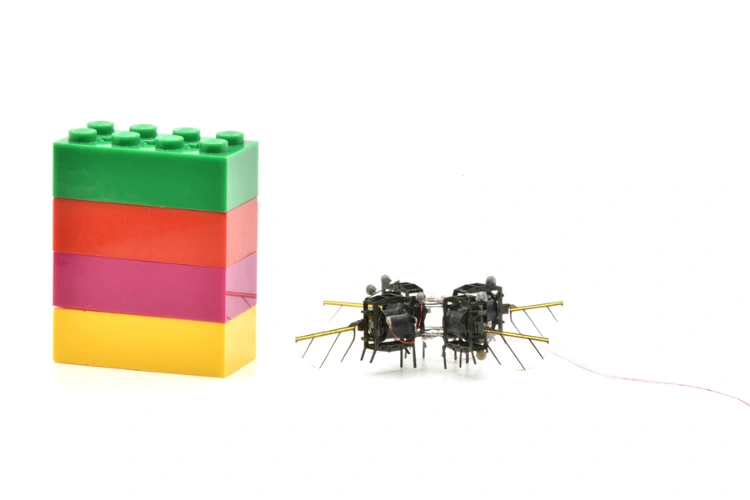

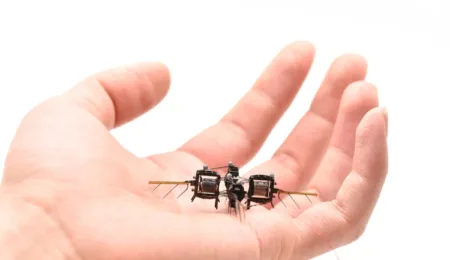

With bee populations declining at an alarming rate, scientists are racing to find solutions before global agriculture suffers irreversible consequences. MIT researchers have been exploring ways to mimic nature’s most efficient pollinators, and in early 2025, they introduced a major breakthrough: ultra-light robotic bees capable of flying 100 times longer than previous prototypes.

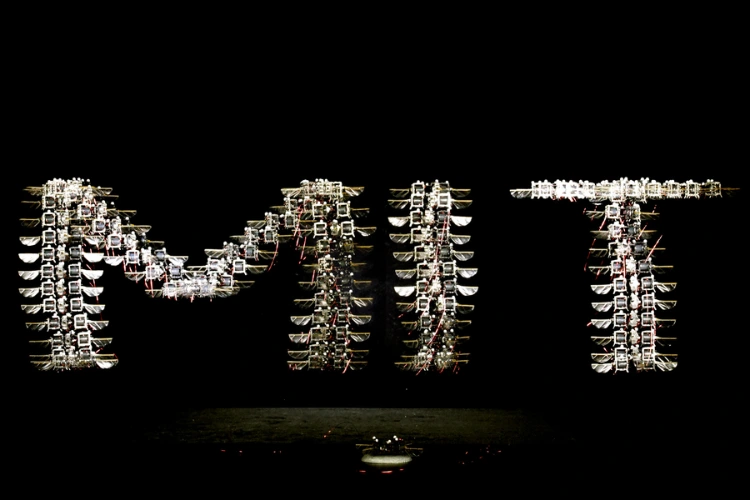

The new prototype can perform complex aerial stunts, including double aerial flips.

Even the most advanced bug-sized robots have struggled to match the endurance, speed, and maneuverability of real pollinators. Now, by studying the anatomy of bees, MIT researchers have completely overhauled previous designs.

The latest version can hover for about 1,000 seconds—more than 16 minutes—compared to just a few seconds in earlier models. Weighing less than a paperclip, the robot can also fly significantly faster (35 centimeters per second) and do a body roll and double aerial flips.

The improvements stem from a major redesign aimed at increasing both flight precision and durability.

The robot’s wings move using artificial muscles, which work like tiny, flexible engines. These muscles are made by stacking layers of soft material (elastomer) between two super-thin carbon nanotube electrodes and rolling them into a soft cylinder. When electricity flows through, the muscles quickly squeeze and stretch, creating the force needed to flap the wings.

In older designs, these muscles had trouble handling the high-speed movements required for flight. They would start bending in ways they shouldn’t, making the robot weaker and less efficient.

The new design includes a special system that prevents this unwanted bending, reducing strain on the muscles and allowing them to generate more power for flying.

Additionally, the refined structure leaves enough space to integrate tiny batteries or sensors, which could eventually enable the robot to operate autonomously outside of controlled environments.

These advancements bring MIT’s robotic bees closer to real-world deployment, where they could play a crucial role in agricultural pollination.

MIT’s robotic bees are an impressive technological leap, but they should be seen as a backup plan rather than a replacement.

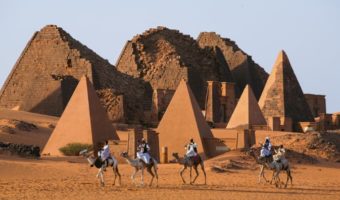

The potential impact of robotic pollinators is hard to ignore. In areas where natural pollinators have disappeared, they could help maintain crop production and food security.

Unlike real bees, they aren’t vulnerable to disease, climate change, or habitat destruction. Farmers could even program them for targeted pollination, optimizing yields for specific crops.

Yet, despite their advantages, robotic bees raise important questions.

The high cost of robotic bees may limit their accessibility for small-scale farmers. And while they might temporarily offset the loss of natural pollinators, they do nothing to restore ecological balance.

Bees support entire ecosystems, contributing far beyond pollination alone. Some experts warn that an overreliance on artificial pollinators could divert attention from conservation efforts, slowing down crucial work to rebuild natural bee populations.