Five Massive Cylindrical Shafts in Tokyo Prevent Flood Damage by Containing Overflow Water

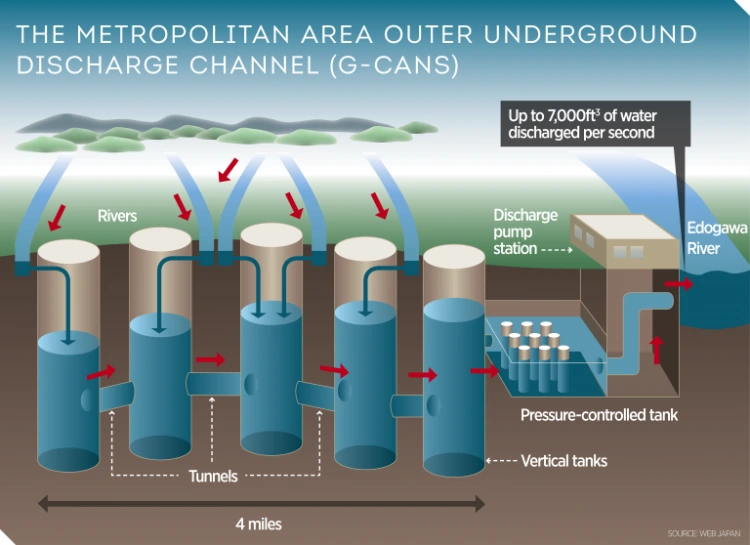

Underneath Japan’s Greater Tokyo Area lies a vast network of towering cylindrical chambers connected to a massive water tank through tunnels. This is Japan’s Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel (MAOUDC), known as “G-Cans,” which protects Saitama Prefecture in Northern Tokyo from flooding.

Tokyo’s Underground Discharge Channel can pump water from a standard 25-meter pool in just three seconds.

On the outskirts of Tokyo, 50 meters beneath the Saitama prefecture in the Greater Tokyo Area, Japan has constructed an engineering marvel that is a subject of awe and amazement among disaster and risk management experts worldwide. It is a testimony to Japan’s proactiveness and its savviness in engineering and technology.

The MAOUDC is a flood diversion facility that drains excess water from northern Tokyo and diverts it to the larger Edo River.

When any of the small and mid-size rivers crisscrossing Tokyo swell and overflow, excess water is drained into one of the five cylindrical chambers constructed along the length of the Discharge Channel.

These chambers, each 70 meters in height, are big enough to accommodate the Statue of Liberty. They are interconnected through tunnels 6.3 kilometers long and 10 meters in diameter.

The water rushes through these tunnels towards the Edo River. But before the floodwater is pumped into the river, it passes through a pressure-adjusting water tank that has become the face of the G-Cans project.

On days when Tokyo is dry, the gigantic water tank becomes a tourist attraction for its cathedral-like appearance, with dozens of 500-ton pillars supporting its high ceiling.

However, when heavy rains pour down and the rivers overflow, the tank slows down the flow of the drained floodwater. This allows the four-pump system to push the floodwater into the Edo River at a speed of 200 tons of water per second. At this rate, the pumps could empty a standard 25-meter pool in just three seconds.

Japan spent $12 billion to build the world’s largest floodwater diversion facility.

While a natural disaster mitigation plan of this magnitude may seem a bit extravagant, Tokyo has historically suffered immense economic damage due to flooding.

With 100 rivers passing through the capital city and four major waterways converging there, rising sea levels and sinking land exacerbate the potential for severe flooding when rains and typhoons provoke it.

Tokyo is a densely populated city with around 37 million people packed into 13,500 square kilometers, and it faces devastating human and economic losses from such flooding.

Japan was early to see the perils of flood and the need to mitigate its damage. Post-World War II, while war-torn nations were rebuilding, Japan began investing 6-7% of its national budget in disaster and risk reduction plans.

In 1993, the G-Cans project was initiated, and after 13 years of non-stop construction and planning, it was completed in 2006 at a cost of $12 billion.

The G-Cans is activated seven times a year on average.

The Discharge Channel was operational in 2002 and has been activated an average of seven times a year since then. The system can withstand 50 millimeters of rain per hour, preventing almost 148 billion yen in damage.

In October 2019, Typhoon Hagibis rigorously tested the effectiveness of the facility.

The typhoon brought record-setting rainfall to Tokyo, resulting in 175.7 million cubic meters of rain in the Nakagawa basin in northern Tokyo. The Discharge Channel drained 27% of that water and prevented flooding by reducing the period when the water level was above the alarming level, from 28 hours to only four hours. Tokyo saved nearly $1.76 billion in flood-related damages.

So far, the MAOUDC has been able to defend the capital from extensive flood damage. However, with the changing weather patterns brought about by climate change, it may not be sufficient in the future.