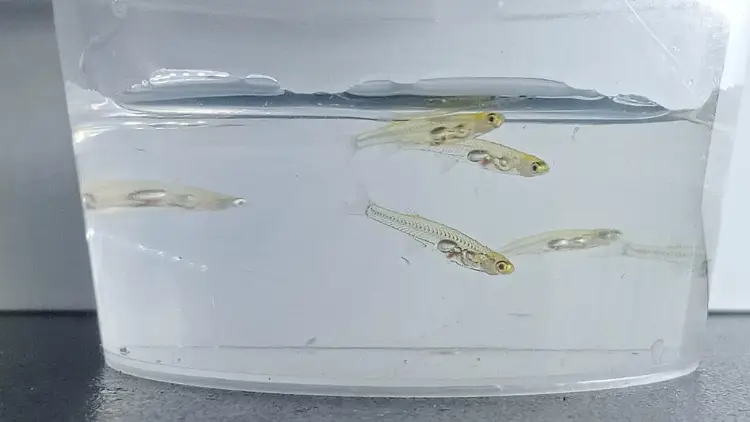

Tiny Fish, the Size of a Fingernail, Can Produce Noises as Loud as an Elephant

A tiny fish, known as Danionella cerebrum, can produce sounds louder than an elephant despite its small size. This fish species only measures half an inch in length and generates noises exceeding 140 decibels. These sounds are comparable to the noise level of a human hearing an airplane take off from a distance of 100 meters. This remarkable ability is quite unusual for an animal of such a small size.

The study, led by ichthyologist Ralf Britz, reveals that Danionella cerebrum‘s sound production surpasses even that of elephants, which can produce sounds up to 125 decibels with their trunks.

Large animals typically produce louder noises than smaller ones, but some small animals defy this trend. For example, snapping shrimp can produce sounds up to 250 decibels using their claws. Similarly, certain fish, such as the male plainfin midshipman fish, can make mating calls reaching 130 decibels. However, Danionella cerebrum stands out among fish for its unique sound production capabilities.

Researchers used various techniques, including high-speed video recordings, micro-CT scans, and genetic analysis, to uncover the mechanisms behind this fish’s sound production. They found that the male Danionella cerebrum possesses a unique sound-generating apparatus consisting of drumming cartilage, a specialized rib, and a fatigue-resistant muscle. These fish produce noise by striking the cartilage against their swim bladder, a gas-filled organ that helps them maintain buoyancy in water. This action generates a rapid pulse, creating the sound.

The study observed that these higher-frequency pulses were produced by alternating compression of the swim bladder from left to right, while lower-frequency pulses were created using repeated compression on the same side. This dual mechanism of bilateral and unilateral contractions allows the Danionella cerebrum to produce a variety of sounds, which they use for communication in murky waters. The researchers hypothesize that the competitive environment among males in such visually restricted settings has driven the development of this specialized acoustic communication mechanism.

This discovery challenges the conventional understanding of vertebrate sound production, which typically involves the manipulation of air by specialized muscles. In contrast, Danionella cerebrum‘s sound production does not involve air movement, highlighting the diverse evolutionary adaptations for communication across different species.